Introduction: Beyond Simple Brackets – Manufacturing Complex Components

The evolution of modern manufacturing has fundamentally altered the role of sheet metal fabrication. Once characterized by the production of simple structural brackets, ductwork, and rudimentary panels, the discipline has transformed into a high-precision science critical to the function of advanced electronics, aerospace systems, and automotive assemblies.1 In the current industrial landscape, original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) no longer view sheet metal merely as a protective skin; it is now an integral component of the device’s thermal management, electromagnetic compatibility (EMI) strategy, and structural integrity. This shift places an unprecedented burden on fabricators to deliver components with micron-level tolerances, utilizing advanced alloys and automated machinery that rival the precision of CNC machining.1

For stakeholders in the electronics and automotive sectors—specifically those tasked with sourcing custom metal enclosures or structural chassis components—understanding the capabilities and constraints of modern fabrication is essential. The gap between a CAD model and a physical part is bridged by a complex series of metallurgical and mechanical processes, each introducing variables that can affect the final product's cost, quality, and performance. Xiamen HYM Metal Group (Hymmetal), with over two decades of experience in the customized manufacturing sector, exemplifies this transition, integrating traditional fabrication with advanced services like die casting and 4/5-axis CNC machining to support industries ranging from medical to military.1

This report serves as an exhaustive technical guide to the precision sheet metal fabrication ecosystem. It moves beyond basic definitions to explore the second-order effects of manufacturing decisions: how the wavelength of a fiber laser influences the micro-structure of an aluminum edge; why the magnesium content in 5052 alloy dictates its bending performance against 6061; and how the choice between welding and self-clinching fasteners alters the total installed cost of an assembly. By examining these factors through the lens of physics, metallurgy, and metrology, we aim to equip engineers and procurement managers with the insights necessary to optimize their enclosure designs for manufacturability and long-term reliability.

Laser Cutting Precision: The Photonics of Tolerance and Edge Quality

The genesis of any precision sheet metal part lies in the cutting process. While traditional methods such as shearing and turret punching remain relevant for specific high-volume or simple-geometry applications, laser cutting has established itself as the preeminent technology for complex, high-precision fabrication. This dominance is driven by the technology's ability to process intricate contours without hard tooling, coupled with a flexibility that supports both rapid prototyping and full-scale production runs.1 However, the "laser" is not a monolith; the underlying physics of the light source—specifically the distinction between CO2 and Fiber lasers—fundamentally dictates the quality of the cut, the achievable tolerances, and the thermal impact on the workpiece.

The Physics of Beam-Material Interaction

To understand precision in cutting, one must first understand the interaction between the photon beam and the metal lattice. The two dominant technologies, CO2 and Fiber lasers, operate at distinct wavelengths that determine their absorption characteristics and, consequently, their efficiency and edge quality across different materials.3

CO2 Lasers: Historically the industry workhorse, CO2 lasers generate a beam by exciting a gas mixture (primarily carbon dioxide) with electricity. This produces light at a wavelength of 10.6 micrometers. This longer wavelength is highly effective for processing non-metals and organic materials, and in the context of metals, it has traditionally excelled in cutting thicker plates (greater than 10mm). The physics of the 10.6-micrometer beam allows for a wider kerf and a heat distribution that, on thick steel, can produce a smoother edge finish compared to early fiber technologies.3 However, the beam delivery system relies on a complex array of mirrors and optics that require precise alignment and maintenance, introducing variables that can affect long-term consistency.

Fiber Lasers: The modern standard for precision sheet metal, particularly for the thin gauges typical of electronics enclosures (0.5mm to 3.0mm), is the fiber laser. These systems generate the beam within an active optical fiber doped with rare-earth elements (such as ytterbium), delivering a wavelength of 1.064 micrometers.3 This wavelength represents a critical advantage: it is an order of magnitude smaller than that of CO2 lasers and is highly absorbed by metals, particularly reflective alloys like aluminum, copper, and brass.

-

Absorption and Speed: The high absorption rate allows fiber lasers to process reflective materials that would otherwise act as mirrors to CO2 beams, potentially damaging the optics. Furthermore, the focused energy density of the fiber laser permits cutting speeds that are often two to three times faster than CO2 counterparts for thin materials, significantly reducing cycle times for high-volume automotive components.3

-

Precision Dynamics: The fiber laser produces a significantly narrower kerf (cut width) than CO2 systems. This narrow kerf is instrumental for nesting parts closely to maximize material yield and for cutting intricate features, such as fine ventilation grilles in electronics chassis or micro-connector cutouts, where the bridge between features may be as narrow as the material thickness itself.5

The Heat Affected Zone (HAZ): Metallurgical Implications

A frequently underestimated consequence of thermal cutting is the Heat Affected Zone (HAZ). This defines the region of the base metal that has not melted but has undergone changes in microstructure and mechanical properties due to the rapid heating and cooling cycle inherent to the process.6 For precision enclosures, the HAZ is not merely a cosmetic issue; it is a region of metallurgical transformation that can compromise the structural and chemical integrity of the part.

Metallurgical Transformation:

The intense localized heat of the laser beam creates a steep thermal gradient. As the laser passes, the surrounding metal acts as a heat sink, causing the cut edge to cool rapidly (quenching). In carbon steels, this can lead to the formation of martensite, a hard but brittle crystalline structure. If a designer places a bend line too close to a laser-cut edge, this brittle HAZ acts as a stress concentrator, significantly increasing the probability of micro-cracking during the forming process.6

Material-Specific Sensitivities:

The severity and impact of the HAZ vary dramatically depending on the thermal conductivity and phase-change characteristics of the material:

-

Aluminum Alloys: Aluminum is highly conductive and reflective. The low melting point combined with high thermal conductivity means heat dissipates rapidly into the surrounding sheet, potentially widening the HAZ if parameters are not tightly controlled. This is particularly problematic for alloys like 6061, where the heat can over-age the precipitates near the edge, locally reducing strength.6

-

Stainless Steel: While less conductive than aluminum, stainless steel is susceptible to chromium carbide precipitation in the HAZ, which can deplete the grain boundaries of corrosion-resistant chromium. For medical or marine enclosures, this sensitization can lead to intergranular corrosion long before the bulk material fails. Thin gauges are also prone to thermal distortion or "oil-canning" due to the residual stresses induced by the HAZ.6

-

Copper and Brass: These materials possess extremely high thermal conductivity, which draws heat away from the cut zone very efficiently. While this might seem beneficial, it actually requires higher power input to maintain the melt, which can result in a wider zone of thermal influence if the laser dwell time is not minimized.6

Downstream Effects:

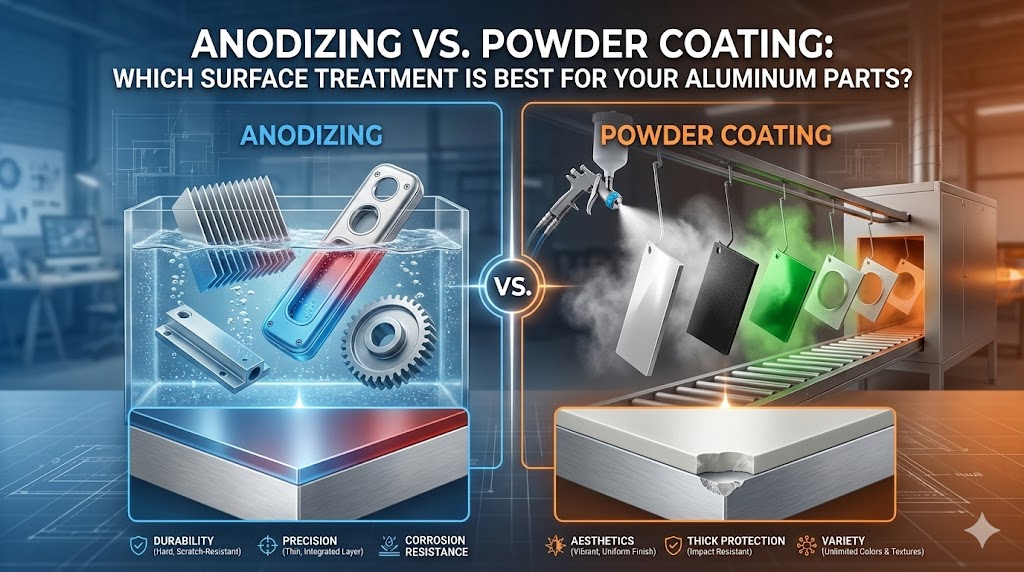

The implications of HAZ extend to secondary processes. For welded enclosures, the oxide layer and altered grain structure of a laser-cut edge can introduce contaminants into the weld pool, leading to porosity or lack of fusion. Consequently, critical weld seams often require a secondary grinding operation to remove the HAZ, adding cost and time to production. Similarly, for parts undergoing anodizing, the HAZ often reacts differently to the electrochemical bath, resulting in a visible "halo" or discoloration along the edge that may be unacceptable for high-end consumer electronics.6

Tolerance Frameworks: ISO 9013 and the "10% Rule"

In the realm of precision fabrication, "tolerance" is a function of material thickness and process capability. To standardize expectations between fabricators and engineers, the industry relies on ISO 9013, which defines quality classifications for thermally cut surfaces. This standard provides a rigorous framework for assessing feasibility, moving beyond vague requests for "high precision" to quantifiable metrics.4

The Physics of Tolerance Degradation:

ISO 9013 acknowledges a fundamental physical reality: maintaining tight tolerances becomes exponentially more difficult as material thickness increases. As the laser beam penetrates deeper into the material, diffraction and thermal blooming cause the beam to diverge. This results in a slight taper in the cut profile (the kerf is wider at the top than the bottom) and increases the variability of the edge position.4 Additionally, the sheer volume of molten material that must be ejected from the kerf in thicker plates introduces turbulence, leading to rougher striations on the cut face.

Standard vs. High Precision:

The achievable tolerances for laser cutting are generally categorized by thickness ranges. A "Standard" tolerance reflects typical commercial production speeds, while "High Precision" implies slower cutting speeds, frequent lens cleaning, and machine calibration to push the limits of the technology.8

Table 1: Laser Cutting Tolerances by Material Thickness (ISO 9013 Derived)

| Material Thickness (mm) | Standard Tolerance (mm) | High Precision Tolerance (mm) | Physical Constraint |

| 0.5 – 2.0 | ± 0.10 | ± 0.05 | Minimal beam divergence; HAZ is negligible. |

| 2.0 – 5.0 | ± 0.15 | ± 0.10 | Slight taper begins; thermal expansion becomes a factor. |

| 5.0 – 10.0 | ± 0.25 | ± 0.15 | Striations on edge become visible; kerf width increases. |

| > 10.0 | ± 0.45 | ± 0.20 | Significant thermal input; edge squaring is required for precision fits. |

7

The "10% Rule" Heuristic:

For engineers designing without access to specific machine data, a practical industry rule of thumb is that the achievable tolerance for standard commercial laser cutting is approximately 10% of the material thickness.4 For example, a 3mm stainless steel bracket would typically be held to a tolerance of ±0.3mm. Requests for tolerances tighter than this benchmark—such as holding ±0.05mm on a 6mm plate—require specialized setups, reduced cutting speeds, and potentially secondary machining operations, all of which drive up the unit cost significantly.4

The Art of Bending: Avoiding Aluminum Cracking and Springback

Once the intricate profile of the enclosure has been cut, the fabrication process moves to forming. Bending sheet metal is a process of controlled failure; the material must be stressed beyond its yield point to induce plastic deformation, but kept below its ultimate tensile strength to prevent fracture. This delicate balance is governed by the material's metallurgy, the geometry of the tooling, and the elastic recovery known as springback. For electronics enclosures and automotive components, aluminum is the material of choice, yet its behavior during bending creates specific challenges that designers must navigate.9

Metallurgical Selection: The 5052 vs. 6061 Trade-off

The selection of aluminum alloy is often the single most critical decision determining the manufacturability of a sheet metal part. While both 5052 and 6061 series aluminum offer desirable properties like corrosion resistance and high strength-to-weight ratios, their microstructures behave fundamentally differently under bending stress.9

Aluminum 5052: The Forming Specialist

The 5052 alloy, with magnesium as its primary alloying element, is the gold standard for sheet metal enclosures that require complex forming.

-

Microstructure: It possesses a grain structure that allows for significant dislocation movement, giving it excellent ductility and formability.

-

Performance: It can be bent to very tight radii—often equal to the material thickness (1T)—without cracking. This property is indispensable for complex chassis designs involving hems (folded edges), offsets, or multiple bends in close proximity.9

-

Durability: Its high fatigue strength and resistance to saltwater corrosion make it the preferred choice for marine electronics and automotive components exposed to road salts.11

-

Limitation: It is a non-heat-treatable alloy. It achieves strength only through strain hardening (cold working), meaning it generally has a lower ultimate tensile strength compared to heat-treated 6061.

Aluminum 6061: The Structural Standard

The 6061 alloy, alloyed with magnesium and silicon, allows for precipitation hardening (heat treatment), most commonly found in the T6 temper.

-

Microstructure: The T6 heat treatment creates rigid precipitates within the grain structure that block dislocation movement, significantly increasing yield strength but drastically reducing ductility.

-

The Cracking Phenomenon: Because of its brittle nature in the T6 state, 6061 cannot accommodate the tensile strain on the outer radius of a tight bend. If forced into a sharp bend (e.g., 1T radius), the grain boundaries separate, leading to visible cracking or complete fracture.9

-

Design Implications: Bending 6061-T6 requires a minimum bend radius of at least 3 to 4 times the material thickness (3T-4T). Alternatively, the material must be annealed to the 'O' temper (soft state) before bending and then re-heat-treated, a process that adds significant cost and can induce warping.9

-

Usage: Consequently, 6061 is typically reserved for machined base plates, heavy-duty structural brackets, or flat panels where rigidity is paramount and forming is minimal.11

Table 2: Minimum Bend Radius Coefficients for Aluminum Alloys

(Expressed as a multiple of material thickness, T)

| Alloy & Temper | 0.032" - 0.063" (0.8-1.6mm) | 0.090" - 0.125" (2.3-3.2mm) | 0.190" - 0.250" (4.8-6.4mm) |

| 5052-H32 | 1.0 T | 1.5 T | 2.0 T |

| 6061-T6 | 3.0 T - 4.0 T | 4.0 T - 5.0 T | 5.0 T - 6.0 T |

| 3003-H14 | 0.5 T | 1.0 T | 1.5 T |

13

Strategic Insight: A common error in enclosure design is specifying 6061-T6 for a chassis with intricate folds to "increase strength." In reality, the necessary large bend radii (to prevent cracking) consume valuable internal volume and complicate the mating of corners. For most electronics enclosures, 5052-H32 provides the optimal balance of formability and sufficient structural rigidity.12

The Mechanics of Springback and Compensation

One of the most persistent challenges in precision bending is springback—the tendency of the metal to return to its original shape after the bending force is removed. This is an elastic recovery phenomenon caused by the residual stress distribution across the sheet thickness.16

The Neutral Axis Shift:

When sheet metal is bent, the material on the inside of the bend radius undergoes compression, while the material on the outside is subjected to tension. Between these zones lies the "neutral axis," where no deformation occurs. During plastic deformation, the elastic core of the material (which has not yielded) stores energy. When the punch retracts, this elastic core attempts to return to equilibrium, forcing the plastically deformed outer layers to move with it, causing the bend angle to "spring back" or open up.17

Factors Influencing Springback:

-

Yield Strength: Materials with higher yield strength (like Stainless Steel or 6061-T6) exhibit greater springback because they have a larger elastic region before plasticity occurs.

-

Bend Radius: A larger bend radius relative to thickness (R/T ratio) results in less plastic deformation and more elastic recovery, increasing springback.18

-

K-Factor Variability: The K-factor is a mathematical constant representing the location of the neutral axis. Slight variations in material thickness or hardness within a single batch can alter the effective K-factor, causing angle inconsistencies from part to part.16

Compensation Strategies:

Fabricators employ sophisticated compensation methods to achieve precise angles:

-

Over-bending: To achieve a 90° finished angle, the operator might program the press brake to bend the part to 88° or 89°, anticipating a 1-2° springback. Modern CNC press brakes often have laser angle measurement systems that measure the springback in real-time during the first bend and automatically adjust the depth for subsequent parts.16

-

Coining: In this method, the punch bottoms out in the die with high tonnage, physically compressing the material to thin it at the bend point. This breaks the elastic memory of the structure, virtually eliminating springback. However, coining requires significantly higher tonnage and can mar the surface of the part, making it less suitable for cosmetic enclosures.19

Deep Box Forming and Tooling Constraints

Manufacturing deep electronic enclosures—such as server chassis or NEMA-rated industrial control boxes—introduces geometric constraints that standard tooling cannot accommodate. The primary challenge is collision: as the sides of a box are bent upward, they can physically interfere with the body of the press brake ram or the tooling holder.20

The Geometry of Collision:

When forming a four-sided box, the first two bends are straightforward. However, for the third and fourth bends, the already-formed sides must swing up as the flange is bent. If the box is deep, these sides will hit the upper beam of the machine before the bend is completed, making the part impossible to form with standard straight punches.20

The Gooseneck Punch Solution:

To circumvent this, fabricators utilize "Gooseneck" punches. These tools are engineered with a deep, curved relief cutout (resembling the neck of a goose) on the back side of the punch body.

-

Function: The cutout provides a spatial pocket that allows the return flange of the box to curl inward without contacting the tool steel. This geometry is essential for forming U-channels, deep chassis, and boxes with inward-facing flanges.22

-

Structural Limitations: Due to their recessed geometry, gooseneck punches have less cross-sectional mass than straight punches, making them weaker. They are typically rated for lower tonnage, limiting their use to lighter gauge materials (like the 1-2mm aluminum typical of enclosures) rather than heavy structural plate.23

Segmented Tooling:

For complex box shapes, the length of the punch must match the internal width of the box exactly to avoid interfering with the perpendicular sides. Fabricators use "window" or segmented tooling—punch and die sets broken into modular lengths (e.g., 10mm, 20mm, 50mm, 100mm). The operator assembles these segments to create a custom tool length that fits precisely inside the box, allowing for the formation of the final sides without crushing the adjacent flanges.21

Assembly and Fastening: Architecture for Electronics

The structural integrity and functionality of an enclosure are ultimately defined by how its constituent parts are joined. In the context of electronics and automotive assemblies, the choice of fastening method dictates not only the mechanical strength but also the electrical continuity (grounding), serviceability, and total manufacturing cost. The three dominant methods—welding, riveting, and self-clinching fasteners—each offer distinct advantages depending on the application requirements.24

Comparative Analysis: Riveting, Welding, and PEM Fasteners

1. Welding (TIG/MIG/Spot): The Permanent Seal

Welding provides the highest ultimate strength and is the only method that can create a hermetically sealed joint, which is a prerequisite for high-IP-rated enclosures (IP66/67) designed for outdoor or harsh environments.

-

Performance: A continuous seam weld creates a unified structure that is impervious to moisture and highly resistant to vibration fatigue.

-

The Hidden Cost: While the consumables are cheap, welding is labor-intensive and thermally destructive. The high heat input creates a significant Heat Affected Zone (HAZ), which can distort thin sheet metal (oil-canning) and destroy pre-existing coatings like galvanization or anodizing. This necessitates expensive secondary operations: grinding down weld beads, polishing to remove heat tint, and re-plating or painting the entire assembly.24

-

Aluminum Challenges: Welding aluminum enclosures is particularly demanding due to the oxide layer, which melts at a much higher temperature than the base metal. This often requires alternating current (AC) TIG welding to clean the oxides, a process that requires high operator skill to avoid burn-through on thin chassis.6

2. Riveting (Blind/Solid): The Cold Mechanical Joint

Riveting is a "cold" joining process, meaning it introduces no thermal distortion.

-

Versatility: It is excellent for joining dissimilar materials, such as attaching a plastic fan shroud to an aluminum chassis, where welding would be impossible.

-

Constraints: Rivets are permanent but not flush. The protruding heads can interfere with internal components or ruin the external aesthetic of a consumer device. Furthermore, blind rivets can leave a remnant of the mandrel head loose inside the enclosure, posing a Foreign Object Debris (FOD) risk that is unacceptable in high-reliability electronics.24

3. Self-Clinching Fasteners (PEM® Nuts): The Electronics Standard

For the electronics industry, self-clinching fasteners (often referred to generically by the brand name PEM®) represent the gold standard for component mounting. These are hardened steel fasteners that are pressed into a pre-punched hole in a ductile metal sheet.26

-

Mechanism of Cold Flow: The fastener features a displacer (knurl or rib) and an undercut (shank). When pressed, the displacer pushes the sheet material into the undercut. This "cold flow" of the ductile sheet locks the fastener permanently in place, providing high torque-out and push-out resistance.26

-

Benefits for Enclosures:

-

Serviceability: They provide robust, reusable metal threads in thin sheets (down to 0.5mm) where tapped threads would strip instantly. This allows for repeated removal of cover panels for maintenance.25

-

Flush Mounting: Many designs install flush on the reverse side, allowing for smooth exterior cosmetic surfaces or tight stacking of internal PCBs.26

-

Conductivity: Because they bite into the base metal, PEM nuts provide excellent electrical continuity, essential for creating grounding points for EMI shielding.27

-

-

Total Cost Analysis: Although a PEM nut costs more per unit than a spot weld, the Total Installed Cost is often 20-40% lower. This is because they eliminate the need for post-weld grinding, cleaning, and re-tapping of distorted threads. They can also be installed automatically in the punch press (in-die), drastically reducing manual labor.28

Table 3: Fastening Method Comparison for Enclosures

| Feature | Welding (Spot/Seam) | Self-Clinching (PEM) | Riveting (Blind) |

| Strength | Excellent (Fused) | Good (Mechanical) | Moderate |

| Serviceability | Permanent (Destructive removal) | Reusable Threads | Permanent (Drill out) |

| Heat Distortion | High (HAZ risk) | None (Cold process) | None (Cold process) |

| Waterproofing | Excellent (Seam weld) | Poor (Unless sealed) | Poor (Hole leak) |

| Post-Processing | High (Grinding/Polishing) | Low/None | Low |

| Aesthetics | Seamless (after finishing) | Flush/Low Profile | Protruding Head |

24

Specialized Assembly Techniques for Electronics

Grounding and Bonding:

For automotive and industrial electronics, safety standards and EMI reduction require low-impedance ground paths throughout the enclosure.

-

Masking: When using PEM nuts on powder-coated panels, the contact area must be masked during painting to ensure metal-to-metal contact. Alternatively, "grounding" nuts with sharp teeth can be used to bite through the paint or oxide layer to establish continuity.29

-

Bonding Straps: In hinged doors, the hinge itself is not a reliable ground path due to lubrication or clearance. Dedicated flexible braiding (bonding straps) must be welded or bolted across the hinge to ensure the door acts as part of the Faraday cage.31

Circuit Board Integration:

Hardware selection extends to PCB mounting. Keyhole standoffs allow a circuit board to be slipped over the fastener heads and locked in place by sliding, rather than requiring the removal of four screws. This "tool-less" design is increasingly favored for server racks and automotive modules where field replacement speed is critical.27

Sheet Metal Quality Control: Flat Pattern Verification

In precision fabrication, quality control begins long before the metal is cut. The fundamental challenge of sheet metal is the geometric transformation from 2D to 3D. A defect in the mathematical "unfolding" of the part will result in a physical component that is dimensionally incorrect, regardless of how precise the laser cutting or bending machinery is.

The Mathematics of the Flat Pattern

The "Flat Pattern" is the 2D geometry sent to the cutting machine. It is not simply the 3D dimensions flattened out; it must account for the stretching of the material during bending.

-

Bend Deductions: As metal bends, it elongates. The fabricator must subtract a specific amount of material (the Bend Deduction) from the total length to ensure the final folded dimensions are correct.

-

The Verification Gap: A common failure mode occurs when a designer uses a generic K-factor (e.g., 0.44) in their CAD software, while the fabricator uses tooling that produces a different radius (and thus a different stretch). If the flat pattern is not verified against the specific tooling library of the shop, features like holes located near bends may drift out of tolerance or deform into ovals.32

-

Visual Validation: Before cutting, engineers must inspect the flat pattern for collisions—situations where flanges might overlap in the flat state or where bend reliefs are missing, which would physically tear the metal during forming.33

Automated Optical Inspection: FabriVISION

For First Article Inspection (FAI) and ongoing production quality, manual measurement with calipers is insufficient for complex profiles. The industry has adopted automated optical inspection systems, such as FabriVISION, to digitize quality control.

-

Technology: These systems use high-resolution laser scanners to capture the complete profile of a flat part placed on a glass table.

-

Process: The scanned image is overlaid digitally against the original CAD DXF file. The software performs a best-fit analysis, highlighting any deviations in color-coded maps.

-

Precision: It can detect errors as minute as ±0.05mm in hole position, perimeter profile, and feature size, covering 100% of the part geometry in seconds rather than the hours required for manual inspection.34

-

Reverse Engineering: Beyond inspection, these systems can scan a physical template (e.g., a legacy automotive gasket or panel) and generate a CAD file, enabling the re-manufacturing of parts for which original drawings have been lost.35

Design for Manufacturability (DFM): Enclosure Optimization

Creating a sheet metal enclosure that meets the stringent requirements of IP ratings (Ingress Protection), EMI shielding, and vibration resistance requires a holistic DFM approach. The design must anticipate the limitations of the manufacturing process to ensure reliability in the field.

Ingress Protection (IP) and Corner Design

For enclosures destined for outdoor use (NEMA 4 / IP65) or industrial wash-down zones (IP66), the corner design is the critical vulnerability.

-

Welded Corners: The traditional and most robust method for waterproofing is to fully seam weld the corners where flanges meet. This guarantees a continuous barrier but is the most expensive option due to the manual welding and finishing required.36

-

Interlocking Flanges: For cost-sensitive applications (NEMA 1 or IP54) where complete waterproofing is not required, interlocking or "mitered" flanges are used. The flanges are designed to overlap, creating a tortuous path for dust and EMI without the need for welding.37

-

Bend Relief Strategies: To prevent the metal from tearing at the corner where two bend lines meet, relief cuts are essential.

-

Rectangular Relief: The simplest to cut but creates sharp internal corners that act as stress risers.

-

Tear Drop Relief: For high-vibration automotive environments, a "tear drop" or obround relief is preferred. It eliminates the sharp corner, distributing stress more evenly and significantly reducing the risk of fatigue cracking over the vehicle's life.38

-

EMI Shielding and Gasket Architecture

Electromagnetic Interference (EMI) shielding is a non-negotiable requirement for automotive ECUs and telecommunications equipment.

-

The Faraday Cage: The enclosure acts as a conductive shield. To be effective, any gaps or seams (such as door edges) must be smaller than one-quarter of the wavelength of the interference frequency.

-

Material Choice: Aluminum (5052) and Copper are excellent for shielding due to their high conductivity. Stainless steel is durable but less conductive; tin-plated steel is often used as a cost-effective alternative that balances corrosion resistance with surface conductivity.40

-

Gasketing Design: Conductive gaskets (metal mesh or conductive elastomers) are used to seal removable panels. A critical DFM feature is the "compression stop." The sheet metal design must include physical features (like dimples or a specific channel depth) that prevent the gasket from being over-compressed. Over-compression can crush the conductive elements, destroying the shield, while under-compression leaves gaps that leak radiation.41

Automotive Vibration Resistance (SAE J1455)

Enclosures mounted on heavy-duty vehicles must survive punishing vibration profiles defined by standards like SAE J1455.42

-

Stiffening Geometry: Large flat panels are prone to "oil-canning" and resonance. DFM for automotive enclosures involves adding "cross-breaks"—gentle pyramid-like creases stamped into large panels. These creases increase the stiffness of the panel and shift its natural frequency away from the resonant frequencies of the vehicle engine/suspension, preventing fatigue failure.43

-

Fastener Locking: Standard nuts will vibrate loose. Automotive designs must specify locking PEM nuts (which use deformed threads to grip the screw) or replace screws entirely with rivets for permanent structural joints.24

-

Mounting Logic: The mounting points should be located near the rigid frame of the vehicle rather than on flexible body panels to minimize vibration amplification.

Conclusion

Precision sheet metal fabrication is a discipline of interconnected variables where physics, metallurgy, and geometry converge. The decision to employ a fiber laser influences the edge metallurgy; the magnesium content of 5052 aluminum dictates the feasibility of a complex bend; and the selection of self-clinching fasteners determines the long-term serviceability and assembly cost of the final product.

For manufacturers in the electronics and automotive sectors, the path to a successful enclosure lies in recognizing these dependencies. It requires a shift from viewing fabrication as a commodity process to treating it as a strategic partnership. By engaging with fabrication experts early in the design phase—leveraging the specific capabilities of advanced machinery like 5-axis CNCs and automated optical inspection—engineers can navigate the trade-offs between cost and performance. The result is not just a metal box, but a precision-engineered component optimized for the rigorous demands of the modern world.

Call to Action

Send us your enclosure designs for manufacturing review.

To ensure your next project meets the rigorous standards of modern manufacturing, contact the engineering team at Hymmetal. We are ready to optimize your prints for precision, cost efficiency, and scalable production.